Seed Conference Speech

By Kent Whealy

This speech was given at the 1985 Seed Conference held on October 4-6 at the Missouri Botanical Garden in St Louis, Missouri. It was co-sponsored by the National Gardening Association (formerly “Gardens for All”) and the Missouri Botanical Garden. Funding for the Conference was provided by the Wallace Genetic Foundation, a branch of Pioneer Hi-Bred. The conference brought together the owners and directors of small alternative seed companies and preservation projects with representatives from the major seed companies.

My name is Kent Whealy and I’m the director of a non-profit organization of vegetable gardeners known as the Seed Savers Exchange. The Seed Savers Exchange is actually a preservation project which is trying to save endangered vegetable varieties. We believe that the majority of the vegetable varieties currently available to gardeners may be lost within a few short years unless drastic action is taken. We are actually working with two groups of seeds: heirloom varieties, which are seeds that have been passed down from generation to generation within certain families, and commercial varieties, which are about to be dropped from seed catalogs. My talk this morning will focus mainly on the latter, especially on a book entitled The Garden Seed Inventory which I compiled and recently had published. But I also want to give you an overview of the work that the Seed Savers Exchange is doing.

I’m not a scientist and I’m not a plant breeder. I’m a gardener. Some of my earliest memories are in a garden, so I’ve been around the love of gardening all of my life. And I was also brought up in a family that was very conservation-minded, so that was also instilled in me quite early…. To digress for a moment, I remember as a kid that I always disliked having to pick the beans. And now I have a bean collection that numbers 2,200 accessions …(laughter)… Anyhow, my involvement with heirloom seeds began quite by chance. In the early 1970s my wife and I had just moved to the northeast corner of Iowa. It’s a beautiful area of limestone bluffs and clear streams and dairy farms near the Mississippi River where Iowa and Wisconsin and Minnesota meet. We were newly married and were planting our first garden together. Diane’s grandfather, an old fellow named Baptist Ott, took a liking to us and was teaching us some of his gardening techniques. He was a really ornery old fellow and was the best storyteller I ever met. We became really close.

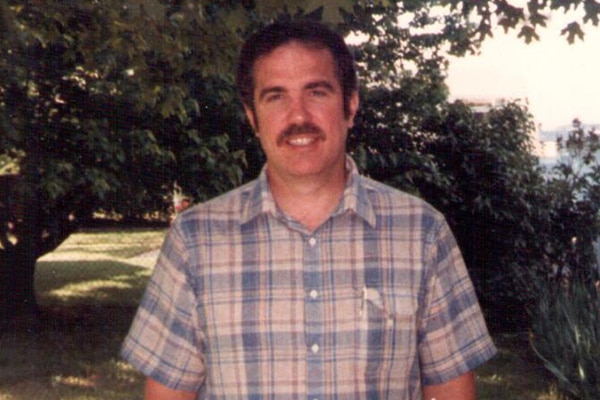

Drawing based on photo of Kent’s father, Arthur Whealy, passing on seeds to Kent’s son, Aaron Whealy

That fall he gave me the seed of three garden plants that his family had brought with them from Bavaria four generations before. He gave me the seed of a large pink German tomato, which was a potato-leaf type. He gave me the seed of a small, delicately beautiful morning glory, which was purple and had a red star in its throat. He also gave me the seed of a strong-climbing prolific little pole bean. Well, the old man didn’t make it through that winter and I realized that, if his seeds were to survive, it was up to me.

About that same time I was lucky enough to come across the writings of Dr. Garrison Wilkes, whom I am very pleased to have finally met this weekend, and also the writings of Dr. Jack Harlan, recently retired Professor of Plant Genetics at the University of Illinois. These two scientists have been trying for decades to warn the public about the dangers of genetic erosion. Their writings have had a profound influence on my work.

At that point I had no idea how prevalent heirloom seeds were, but it was obvious from what I’d seen in Baptist Ott’s garden that the ones I’d been given were excellent. I began to wonder how many other people might also be keeping seeds which had been passed down to them by their families. I also wondered how often, when elderly gardeners pass away, the seeds which they had bred up and selected for a lifetime might sit in a can in a shed somewhere until they died too. So I decided to write to gardening and back-to-the-land magazines in an attempt to locate other gardeners who were also keeping heirloom seeds.

During these past 10 years I’ve discovered that heirloom vegetable varieties aren’t common, but they are also not all that rare. When a person decided for whatever reason to immigrate to the United States — to become a stranger in a strange land — gardeners would invariably bring seeds with them. Seeds are a link to their past and ensure that they can continue to enjoy their foods from the old country. So the Italians brought paste tomatoes, the Germans brought cabbage, the Mexicans brought chiles, and the Russians brought rye and wheat. And these seeds have been smuggled into this country in the linings of suitcases, under the bands of hats, and in the hems of dresses. I’m sure that gives the USDA quarantine people nightmares …(laughter)… but that is the way it has happened down through the centuries and that’s the way it is still happening today. We have seeds within our organization that supposedly were brought over on the Mayflower and we also have seeds that were brought over from Laos last year by the boat people.

We have focused on trying to locate gardeners who are keeping seeds of vegetable varieties that are family heirlooms, traditional Indian crops, garden varieties of the Mennonite and Amish, varieties that have been dropped from all catalogs, outstanding foreign varieties. Essentially, any vegetables seeds that are not available commercially here in the United States. We have found that whenever we go into an area where people are really isolated, we often find a real treasure trove of seeds. That isolation can take various forms. Often it is geographical. The rugged backwoods areas of the Ozarks and the Smokies and the Appalachian Mountains are extremely rich in heirloom varieties. Isolation can also be religious. It has been extremely difficult to penetrate such communities, but slowly we are beginning to see among our members more Mennonite, Amish, Dunkard and Hutterite gardeners. And as trust has built in the Seed Savers Exchange, we are also beginning to gain more Indian members. I am particularly pleased with this, because many Indian peoples are often reluctant to share their seeds. They believe that their seeds are sacred and well they should, because seeds are the sparks of life that feed us all. I am really encouraged that traditional people and ethnic groups have enough trust in the Seed Savers Exchange to be willing to join. At the same time, though, I know that misuse or overuse will quickly drive away these more cautious members.

I have been quite successful in locating gardeners who are keeping heirloom seeds and have organized them into an annual seed exchange. But in the beginning this contacting went quite slowly and by the end of the first year I had located only five other gardeners who were also keeping heirloom varieties. That winter we corresponded with each other and traded seeds through the mail. The next spring one of our group, an elderly woman from Missouri, passed away, but by then three of us were growing the Bird Egg bean that her grandparents had brought to Missouri in a covered wagon in 1858. I kept right at it and by the end of the second year there were 29 of us. That year I published a six-page newsletter …well… to be quite honest, I ran off copies on an unguarded Xerox machine in a place where I was working ….(laughter)… By the end of the third year there were 140 of us. And the more energy I poured into it, the more it grew.

We publish a “Winter Yearbook” each January and 1985 is our tenth year. This is a copy of The 1985 Winter Yearbook. Actually this is a newsletter that has gotten completely out of control …(laughter)… It’s 256 pages long, contains the names and addresses of 550 members, lists of the seeds each has to trade, and lists of varieties they are trying to locate. This year we compiled the yearbook entirely on computer, so it is completely cross-referenced. There is an index in the front which lists each of the about 3,500 vegetables by name and that is followed by codes that show which members are offering seeds of that variety. So you can look up a variety in the index, then turn back to that member’s listing to read their description of the plant.

This yearbook is actually just a formalization of the type of trading that has gone on over the back garden fence for centuries. All across our country, elderly gardeners are keeping collections of unique vegetables that have been adapting for lifetimes to local weather and building resistance to local diseases and insects. In many cases these seeds have been grown by the same family and in the same location for 150 years or longer, always being passed to the next generation. But our society has become so mobile that most families move every few years and many of these master gardeners have no one to pass their seeds on to. So this is the gap that the Seed Savers Exchange is bridging. Right now we must help with this handing-down process or thousands of heirloom vegetable varieties will be lost during the next generation.

During these past ten years, our members have made seed available for an estimated 250,000 plantings of varieties that were not available from any commercial source and many of which were literally on the edge of extinction. It is difficult even for me to imagine the impact that such an exchange is having. And the material we have been able to locate thus far represents really just the tip of the iceberg. Even with 550 members, that’s only an average of 10 per state. Try to imagine what is still out there, at least for the time being. There has never been a systematic large-scale search for heirloom plant material in the U.S. One of the most lasting contributions that the Seed Savers Exchange makes may be the fielding of several hundred local plant explorers. Many breeders are becoming quite excited about what we have already uncovered, because it is material that they have never seen before, much less been able to work with. And as a gardener I also find this quite exciting, because possibly the efforts of our small dedicated group may double the genetic diversity available to backyard gardeners.

Well, that should give you a fairly good idea of how the Seed Savers Exchange is working to save that unique vegetable heritage. About five years ago I also became concerned about another group of vegetable seeds that are just as endangered and these are the commercial varieties which are currently being dropped from seed catalogs. Many of my members were coming to me quite saddened by the fact that some of their favorite varieties had been dropped and they had no idea whether or not there were other sources for them. It seemed like these losses were escalating, but no overall picture of the seed industry existed which would let us see if these varieties had really been dropped completely from commercial availability. It seemed to me that the only way any of us would be able to get a true picture of what was going on would be to inventory the entire U.S. and Canadian seed industry.

In the spring of 1981 I started trying to obtain every mail-order catalog that I could, no matter how small or obscure. Computer equipment was purchased and I began working on the inventory just a couple of months before the Seed Banks Serving People conference which was held in Tucson in October of 1981. Well, I mistakenly estimated that the inventory could be completed in one year and would include 120 seed companies and 3,000 non-hybrid varieties. It actually took slightly over three years to compile and I finally got it back from the printer last January. This is a copy of The Garden Seed Inventory. It’s an 8 ½ x 11” book of 448 pages. It is an inventory of 239 seed catalogs and it describes the 5,785 non-hybrid varieties that are still being offered in the United States and Canada. Each listing includes the variety name, range of days to maturity, a list of all its known sources, and the plant’s description. The book is being heralded by both gardeners and scientists as a landmark study.

The greatest value of The Garden Seed Inventory is that it shows which varieties are in the most danger before they are dropped completely. Many gardeners would gladly buy up a supply of seed, if they knew it was about to be dropped. But usually they have no warning that a favorite variety is in danger until it simply doesn’t show up in a particular catalog one year and they are unable to find another source for it. This Inventory shows all of the alternative sources that are still available. Gardeners can now search through all of the non-hybrid varieties being offered to locate ones which are perfect for their local climate and resistant to local diseases and pests. Gardeners in high altitude or northern regions can locate hardy and short season varieties. Concerned individuals in other countries can use it as a model for similar inventories. Preservationists around the world can use it to buy up endangered commercial varieties, while sources still exist, and then permanently maintain them. And, because the Inventory focuses attention on the seeds that are the least available, many small, almost unknown seed companies will be rewarded and strengthened because they are offering unique or regionally-adapted varieties.

The Garden Seed Inventory has made it possible for the first time to accurately assess which varieties are being dropped and how quickly. As it grew towards completion it became increasingly more fascinating and more frightening. Fascinating because, when viewing the entire garden seed industry in detail, the diversity and quality and number of garden varieties now being offered commercially is almost beyond belief. Gardeners in the United States and Canada are truly blessed. But it was also quite frightening because, it is now apparent that over “48% of all non-hybrid garden seeds are available from only one source out of 239 companies!” (Now when I say that, I don’t mean from one “particular” company. I mean that those varieties are down to being offered by one random company out of 239 possible sources.) And if you add in the varieties that are down to being offered by just two sources, that figure goes up to right at 60%

Although the study hasn’t been going long enough to draw any really firm conclusions, it appears that each year we are losing about 5% of everything that is commercially available. But that figure doesn’t really reflect the overall decrease in availability. Many of the varieties, which are now available from one or two sources, were available from six or more sources when I began this study. And most of those companies dropped these varieties just last year. In other words, it appears that the sources of supply for these seeds have already disappeared. Although many of these varieties have not yet been dropped completely, they will be as soon as those few companies sell out their remaining supplies of the seeds. An almost unbelievable amount of loss is possible within the next few years. Hopefully an immediate and systematic effort can still rescue most of these endangered varieties. But there is never any guarantee that any variety offered by a small number of companies will still be available in next season’s catalogs.

There has been only one other complete U.S. inventory of commercially available food plants. In 1903 the USDA published a book entitled American Varieties of Vegetables for the Years 1901 and 1902 by W. W. Tracy, Jr. It included variety names and sources, but no descriptions. This earlier inventory has been studied in depth and then compared to printouts of what is being kept in the National Seed Storage Laboratory in Fort Collins. Only three percent of everything available commercially in 1902 survives today in that government collection! (And if tomato seeds didn’t keep so darn good in cold storage, that figure would be down to about 1.5%.) It’s depressing to see the huge lists of garden varieties available at the turn of the century and realize that almost all of them have been lost forever. Imagine everything that would still be available for breeders to work with today, if the 1901/1902 USDA inventory had been updated annually and if endangered varieties had been systematically procured and maintained.

At this point, even with a tool like The Garden Seed Inventory, we are just picking up the remaining pieces, but we must at least do that and do it quickly. I intend to update this inventory every couple of years and we are using profits from the book to buy up endangered varieties and maintain them within the Seed Savers Exchange. Now that this overall picture of the seed industry exists, I think there are some new choices that need to be made or at least considered. Until The Garden Seed Inventory was completed, there was really no way for a company to tell whether or not they were the only commercial source that was left for a particular variety. Now that this is apparent, I personally believe that it is that company’s responsibility to get a sample of that variety at least into government collections and hopefully into other preservation networks as well. Now I realize that varieties are sometimes dropped because the companies themselves lose their sources of supply for the seeds, but I’m just talking about the cases where it is possible. There are a few companies that have started systematically sending me samples of varieties they are dropping and I certainly appreciate that. We are certainly selling a lot of copies of the Inventory to seed companies and I just hope that they will see it as a preservation tool and not just as a way to check out the competition.

I also think that the government should be purchasing these endangered varieties while sources still exist. What an easy and even relatively inexpensive way to improve existing collections. And a large portion of this material is the result of tax-supported government breeding programs. I would hate to guess how many millions of tax dollars went into breeding this material and it seems inconceivable that it would be allowed to die out. Again, we have been selling quite a few copies of the Inventory to people within the USDA. But I’m not really in close contact with very many people in the NPGS and so I don’t know what decisions are being made about buying up these endangered varieties.

I do know that the book is in the hands of several thousand gardeners and I have been encouraging all of them to buy up as many endangered varieties as they can easily maintain. And as soon as these varieties are dropped completely, my members will be offering them through the Seed Savers Exchange. I’ve bought up nearly 1,500 varieties myself during these last two seasons and will be buying up a lot more this next spring. So that brings my personal collection of seeds to somewhere around 4,000 varieties. From the very beginning, I’ve tried to keep from building up a personal collection, because I realized that it would be all that I could do to just keep up with the publications which provide access to everyone. But that all started to change when I promised John Withee that I would maintain his Wanigan Associates bean collection in 1981. John had spent 14 years building up a fantastic collection of 1,186 accessions. John was wise enough to realize that if his collection was to survive he needed to pass it on, because of age and health problems. And because it was handed over systematically, all of the sources and many descriptions were handed over as well. Often when a collection is transferred it is after the collector dies and much, if not all, of the information is lost, so we were very lucky in that respect. In 1981 I started organizing a Growers Network to multiply John’s collection. About 350 gardeners participated during the summers of 1982 and 1983. In the spring of each of those years I sent out approximately 2,500 packets of beans. The gardeners in the Growers Network multiplied these and then returned them to me.

Recently we switched from a program of grow-and-return to one of long-term maintenance. We ask that the growers “adopt” varieties, maintain them for at least five years before turning them back in, and also make them available to others through their yearbook listing. This system appears to be working much better. Only our more serious members will make that kind of commitment and they represent the core of the organization and intend to participate over the long run. Also if a person agrees to maintain, for example, a half a dozen tomatoes and grows them for five years, that grower “knows” those tomatoes.

As I mentioned before, I am keeping a collection of somewhere around 4,000 varieties. Over half of these are beans and about 600 more are tomatoes. About 70% of these are seeds that members have sent me and the remainder are endangered commercial varieties which we are buying up using the Inventory. Only about 20% of the collection has been adopted, so this summer I joined forces with Glenn Drowns, a young squash collector from Idaho. We rented five acres of rich riverbottom ground and grew out slightly more than 2,000 varieties. We grew over 500 beans, Glenn’s entire collection of 370 squash, 280 tomatoes, 130 potatoes, 120 corns, 120 muskmelons, 115 watermelons, 100 peppers, probably 50 peas, 50 lettuces, and smaller amounts of a lot of different things. All of the corns and all of the cucurbits were hand-pollinated. We also caged all of the peppers against crossing. So we’ve been spending a large part of the summer in the garden …(laughter)…

This Preservation Garden would not have happened, at least not at its present scale, if it hadn’t been for a generous grant from Pioneer Hi-Bred. Their funding defrayed almost half of the project’s total cost and I am very grateful for their support. You know, a lot of people have a really stereotyped view that the large seed companies are concerned just with profits and not with preservation. From my experience, that certainly isn’t the case with Pioneer. I think it’s wonderful to see the strong commitment to genetic preservation they are exhibiting, whether it be their funding of this conference, providing funds for our Preservation Garden, or other projects I know they are supporting. I think they should be quite proud of their efforts and each of us should definitely take notice.

I want to talk a little bit about something that I run into all the time, and I’m sure that a lot of you have trouble with it, too. And that is, how do you explain to other people what we’re all trying to do? I have an especially hard time describing it to people who ask me what I do for a living. If I say, “I’m a networker and I’m putting together various networks of gardeners who are involved with projects having to do with preservation of genetic diversity,” I see their eyes cloud over just immediately. I’ve gotten to the point now that I start off by telling them, “Well, I’m a garden writer.” And they can relate to that. And then, if they should express any more interest, I’ll start gradually telling them more and more about what we’re really doing, but invariably I see their eyes start to glaze over. And I think this is something that we really all run into. As Garrison said yesterday, only 5% of the people in this country make their living producing food. Those folks and gardeners are the only two groups of the general public that are able, from their own experiences, to relate to these issues. It’s hard to motivate people even in situations where they can see that they are in danger. And problems involving genetic diversity are so abstract, that it seems to almost make them invisible.

But I saw something this summer that really may be the answer. I’m very enthusiastic about the way that we were able to use the Preservation Garden to really open people’s eyes. When you take a tour of gardeners out into a garden where there are 2,000 different varieties growing, the effect on them is amazing. Time and again we’d see people walk into that garden, their mouths would fall open, and then they’d get fired up. They’d start looking and they just couldn’t stop. You’ve got to “show” them! We can talk about the loss of genetic diversity until we’re blue in the face, but it’s so abstract that most people fail to even recognize it as a threat. But if you take those same people into a garden, show them hundreds of unique varieties, and tell them that most would be extinct except for our protecting them — then they understand. And I really don’t think that anything we can do will take the place of “showing” people genetic diversity.

We have a Campout Convention each year for our members. This summer it was held on July 20 and 21 at a 4-H Camp which, very conveniently, was just across the fence from our Preservation Garden. This year attendance tripled to about 180. We knocked people’s eyes out with spectacular and unique varieties and also with the sheer size of the plantings. We taught them how to keep their varieties pure by giving hands-on demonstrations of both the hand-pollination of squash and the hand-pollination of corns. We had an excellent lineup of speakers from around the country and slideshows lasted into the night. Mainly we just showed them what can be done and their response and enthusiasm were incredible.

It is this type of growout and educational tours that I want to continue to pursue with the Seed Savers Exchange. My dream is to buy a small fertile farm in northeast Iowa and set it up as an exemplary Preservation Farm. There we will develop huge trial gardens, a system of special greenhouses, and large underground root cellars. We would be able to grow out our huge collection of seeds and evaluate the newly discovered heirlooms that are constantly entering the collection. We will photograph and document and publish descriptions of these plants. Some of the finest young seedspeople in the country have already expressed a desire to be part of such a project. Young people could come during the summer to learn and to work in the gardens as apprentices. The Preservation Farm could include all aspects of genetic conservation, not just vegetables. Orchards, poultry, rare livestock breeds, herbs, and flowers are all facing the same loss of genetic diversity. I would eventually like to see a network of such Preservation Farms, trialing plant material in different climates and sharing data via computers. I intend to be setting up the model for them all within a year.

Dreaming? Sure I’m just dreaming. But I’ve already proven time and again that with a lot of hard work and one-pointed dedication it’s possible to turn such dreams into reality. I personally believe that good people working together toward high goals can accomplish anything, if you can just keep politics and religion out of it …(laughter)… For many of us the garden is our religion. Planting the seeds, seeing them break the soil, watching the plants come to full fruit, marveling at the diversity and the beauty, and then watching it all die back — is a deeply religious experience. There have always been seedspeople like us and there always will be. Those who are totally enthralled with the spark of life that’s in the seeds. Seeds are very sacred. We are the stewards of this invaluable and irreplaceable genetic wealth and we better start acting like. Just try to imagine what it would cost in terms of time and energy and money to breed this many excellent varieties. But they’re already there. All we have to do is save them.