Rescuing Traditional Food Crops in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union

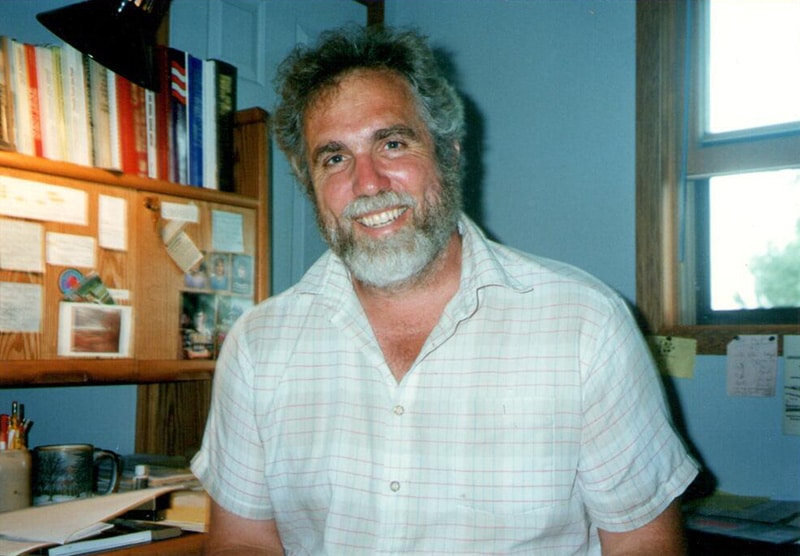

Speech by Kent Whealy at 1993 Campout

As I was considering what to talk about today, I decided to speak – as Wes would say – about my passion, about what’s really driving me these days. So, if you will allow me the liberty of jumping around between various events of the last two years, I’d like to tell you how our international efforts are coming together, and then relate that to some of the new projects that we’re getting into at Seed Savers.

I’ve always wished that my work had started 50 years earlier, when vastly more traditional varieties were still being kept in this country. Seed Savers’ work has been highly successful and is both unique and exemplary, but, when you think about it, we’re really collecting from a fragmented ethnic patchwork that’s almost completely surrounded by mechanized agriculture. There are other regions in the world that are incredibly more rich genetically, and some of those countries have only recently opened their borders to travel by Westerners for the first time in over 70 years.

During these last two years I’ve made three trips to the former Soviet Union and two trips to Eastern Europe, trying to determine if their heritage of traditional food crops is still unbroken in some areas, and also trying to locate that perfect person in each country who would be able to collect for Seed Savers. In general, what I’ve found is that the remaining genetic resources in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union are usually directly linked to the extent of Soviet collectivization of the various farming systems. In Romania, for example, only half of the farms were ever collectivized, and only a quarter of Poland’s farms were collectivized. In the unaffected regions of those countries, traditional agriculture is completely unbroken with most seeds still produced by gardeners and farmers.

I am really concerned that most of those traditional food crops are going to be lost very quickly, as Western agricultural technology floods into those areas along with American, Japanese and Dutch seeds. Therefore, two years ago I set a goal for myself of trying to develop a network of seed collectors who would undertake collecting expeditions in an attempt to rescue traditional food crops in the countries across Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Those efforts are now starting to produce results.

Those of you who were here at last year’s Campout heard Nancy Arrowsmith give the keynote speech. Nancy is an American who has been living in Austria for the past 15 years. About four years ago she started an organization in Austria called “Arche Noah” (which is German for Noah’s Ark) that is based on Seed Savers’ model. Arche Noah already has about 1/10 as many members as Seed Savers and has located about 1/10 as many varieties, but in a country that has only about 1/40 of our population. Nancy has really done an excellent job collecting traditional food crops throughout Austria, and last year she received a Ford Foundation award that named her Conservationist of the Year in Austria. While Nancy was here last summer, our entire staff met with her to try to determine how we might be able to work together to rescue traditional food crops in Eastern Europe. At that time Nancy suggested that the areas where we might make the greatest contribution would be Romania and Poland.

In October 1992, Nancy and I were invited to a conference in eastern Germany for genebanks and nongovernmental organizations. The conference was held on the large island of Rugen off the north shore of what used to be East Germany. Actually, most of the conference took place on the small island of Vilm that had been the vacation hide¬away for Eric Honneker, the corrupt East German leader, who, when the wall came down, fled to Russia with the help of some KGB generals. Because Vilm had been sort of a resort for the Communist elite in East Germany, the island was highly protected and was therefore also a nature preserve. A powerful young environmentalist named Johannes Knapp has a permanent office in one of the nine thatch-roofed cottages on Vilm. Johannes gained international recognition by stopping a ship building facility pro¬posed for the island of Rugen by generating a huge amount of publicity and getting 160,000 signatures on petitions. He took Nancy and me on a hike through a magical 400-year-old beech woods on the island of Vilm that can only be described as a sacred grove. I wish all of you could have been with us, because it was really the most incredibly beautiful woods that I had ever walked through.

During the conference Nancy acted as my translator. We met many scientists who work at various genebanks throughout Eastern Europe, and especially a lot of scientists from Poland. Government seed collections in Eastern European countries are often extremely decentralized, usually without any central storage facility. For example, there are 13 official branches in the Polish germplasm system, and also dozens of other loosely net¬worked breeding projects. Typically, a prominent tomato breeder would have his own project with a crew of scientists and technicians, a large collection of seeds, equipment, greenhouses, laboratories and land, all formerly provided by the State. Now all of that is disintegrating – no money, no land, no co-workers, and all of the older scientists are being forced into early retirement. Delegates at the conference described dozens of instances of valuable breeding collections being sold, plowed under or dumped, but most seed collections are currently in limbo.

The conference was co-sponsored by Gatersleben, the famous genebank in eastern Germany, and by Johannes Knapp’s environmental organization. It was really a thrill for me to be there, because I had been hearing wonderful reports for more than a decade about the work being done by Gatersleben. Immediately after reunification, Gatersleben had to fight for its existence because there was an attempt by the West German seedbank – a facility called Braunschweig – to absorb Gatersleben. During a fierce struggle that ensued throughout 1991, Gatersleben was able to retain its independence but its staff was cut drastically. Within the two-year period after the wall came down, anything that had been West German was incorporated as All-German, and within that same period all East German institutions had to fight for legal basis in order to still exist. For example, Johannes Knapp fought for and obtained legal standing for all East German national parks to become All-German. This struggle was especially difficult for duplicate efforts such as Gatersleben which has had to argue that it has distinct areas of focus that are entirely different from the technocrats at Braunschweig, in order to assure that their research will continue independently. Gatersleben’s main areas of focus are currently forage grasses and forest trees, but the facility is best known for its long history of extremely active efforts collecting food crops throughout the former Communist world.

Just to give you an idea of how fierce the battles have been during German reunification, during the last three years 15,000 agricultural researchers in former East Germany have been cut to 3,000. Dr. Christian Paul from Braunschweig told me that when the wall came down, he was amazed because Braunschweig and other West German facilities were definitely better equipped for high-tech research, but Gatersleben and other East German facilities had nearly eight times as many researchers working on agricultural problems. Although Gatersleben fought successfully for survival and prevailed, they’ve had their staff slashed to only six scientists now working at Gatersleben itself, and five other scientists spread over four small research stations (two at a fruit tree station, and one scientist at the stations with collections of potatoes, cereals and forage crops). Those numbers do not include technicians and seasonal staff who are hired locally. Gatersleben currently is maintaining about 100,000 accessions, but two years from now is scheduled to lose two more scientists.

The director of Gatersleben is Dr. Karl Hammer, a fellow in his late 40’s, about two years older than me. Dr. Hammer has been the head of the genebank at Gatersleben for about three years. During a break at the conference in Rugen, I was walking around a castle grounds with Dr. Hammer and told him about the work that we had been doing here at Seed Savers for the last 18 years. His eyes lit up and he said, “I did similar work myself.” Dr. Hammer had joined Gatersleben’s staff in 1969 as a young scientist, and became quite concerned because the traditional food crops in East Germany were being lost very quickly. He expressed those concerns to his superiors, who didn’t really give him any direct support, but told him that he could go ahead on his own and deal with the situation. So in the early 1970s, Dr. Hammer put notices in East German newspapers and magazines, answered thousands of letters, and collected about 700 varieties of traditional food crops that are still in the collections at Gatersleben. It quickly became apparent that we have found a friend in Karl Hammer who is well aligned with the work that we’re doing here at Seed Savers.

Nancy Arrowsmith translated for the presentation that I made at the Gatersleben conference. The scene was interesting; actually, I think all of you would have found it a bit humorous. We sat through dry presentation after dry presentation for almost two days. When we finally got our chance to speak, it was in the evening of the second day just about dusk. The rapidly fading light in the long hall where we were meeting was just perfect, and we used David Cavagnaro’s slides to really knock their socks off with the incredible beauty of the collections here at Heritage Farm. The crowd had been so stiff up to that point, that it was almost spooky. But, after our presentation, we literally had older scientists coming up to us so excited that they were bouncing up and down. One older fellow told us, “This is exactly what we need! We need to get people excited about genetic resources!” (He had been head of Gatersleben’s potato collection and was forced to retire during staff cuts, but is still working with one young scientist to maintain more than 2,300 varieties, 1,700 of which are in tissue culture.) After we finished, Karl Hammer got up and told the 80 scientists that our message echoed his own feelings and was exactly what he had hoped the conference would convey. From that point on, everyone really opened up to us.

During the Gatersleben conference, we met a young man from the Vavilov Institute who was traveling around to various genebanks in the former republics trying to pull the Vavilov collection back together. I know that most of you have probably read about the Vavilov Institute in previous Seed Saver publications, but, for those of you who haven’t, let me tell the story briefly. Nicholai Vavilov was a renowned Russian botanist and plant collector who taught the world that there are genetic homelands for different crops. Vavilov did his collecting in these centers of origin, or centers of diversity. He started collecting in 1908 and by 1920 had traveled all over the world, including the Americas. Before World War II, Vavilov had been involved in 65 expeditions and had personally collected 165,000 kinds of seeds and plants. Vavilov’s total collection at that time reportedly included 250,000 kinds of seeds and was housed in the Vavilov Institute in Leningrad, which has recently been renamed St. Petersburg.

Vavilov was imprisoned a week before the siege of Leningrad started – because of a dispute over Stalin’s acceptance of the flawed genetic theories of a pseudobotanist named Lysenko – and died of starvation in prison just before the siege ended. During the 900-day siege, which resulted in the deaths of 600,000 Russians, at least 10 scientists died of starvation at their posts in the Vavilov Institute. Vavilov’s staff was surrounded by tons of edible seeds, but believed that they didn’t have the right to eat any seeds in order to survive. In Russia today there’s a tremendous appreciation for that heritage of courage. Nicholai Vavilov is a national hero, and the story of how his staff persevered is held up as a shining example of the Russian will and the value of genetic resources.

But what’s happening now is that there is no long any money available to maintain the collections. During my third trip to Russia in February 1992, I spoke to the botany students and faculty at Moscow State University, to students and faculty at the Timiryasev Agricultural Academy, and also to the staff at the Institute of Vegetable Breeding and Seed Production on the west edge of Moscow. My friend Sergei Smirenski, an ornithologist at Moscow State, translated for all three of my presentations. During our conversations with elderly scientists at the various agricultural institutes, we repeatedly heard their concerns that a substantial portion of Vavilov’s collections might be lost within the next few years. The Russian government had stopped paying any wages to State workers at that point and was just issuing IOU’s. Staffs of scientists were being cut in half, and then cut in half again. Reportedly many of the old people were continuing to grow out the collections of seeds, because they have always maintained the collections and the plants are like their children, but that wouldn’t go on for very long.

As the Soviet Union disintegrated, the Vavilov system was also broken apart. Five of the 17 branches of the Vavilov Institute are now located in newly independent republics, most of which are unwilling to cooperate with the Russian system. So those portions of the collection have been cut off from the Russians. The situation has also resulted in other serious problems, because about 25% of the material remaining in the Russian collections can’t be multiplied in Russia anymore. They need the warmer stations in the southern republics, which are no longer part of the Russian system. So the young Rus¬sian fellow that we met at the Gatersleben conference was attempting to negotiate the return of some portions of the Vavilov collections from the newly independent republics, and I imagine he was there to approach Dr. Hammer about duplicate material that might be in Gatersleben’s collections.

Last March (1993), I made a second trip to eastern Germany and actually went to visit Karl Hammer at Gatersleben, which is about 100 miles southwest of Berlin. I flew into Tegel airport on the northwest side of Berlin where I was met by Nancy Arrowsmith who had arrived that morning by train from Vienna. We rented a car and drove to Schonefeld airport – the former Communist airport on the southeast edge of Berlin – where we picked up Elchin Atababayev, who had flown on Aeroflot from Baku, Azerbaijan to Moscow to Berlin. (I’ll tell you more about Elchin later.) The three of us drove southwest to Magdeburg, then on through the beautiful old city of Quedlinburg, and finally arrived at the nearby village of Gatersleben which isn’t on any map. We drove past what used to be the guardhouse at the edge of the Institute’s compound. Karl Hammer met us in front of the Vavilov Haus (house) where he and his staff have their offices. “Ah, an international delegation,” he said with a mischievous grin, and welcomed us warmly.

We walked into the Vavilov Haus, where we were joined by Dr. Peter Hanelt with whom I’m sure John Swenson has corresponded extensively. Dr. Hanelt is probably keeping the world’s best collection of alliums (onions), and a permanent planting of the hardy selections covers an area about the size of a football field. Gatersleben has an impressive history of collecting expeditions in countries throughout Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, and has also collected heavily in Cuba and in most of the countries that were formerly aligned with the Eastern block. For example, Nancy told me that in Austria almost the entire genebank collection consists of 600 beans collected in Styria (a region in southern Austria) which are the result of a joint collecting expedition between Gatersleben and the Austrian genebank. On the walls of the hallways in the Vavilov Haus were posters of photographs and descriptions of Gatersleben’s plant collecting expeditions to Southwest China, Northwest Mongolia, Georgia, Albania, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, Romania, Korea, Ethiopia, Italy and Cuba. Many excellent books for the general public have been published by or in collaboration with Gatersleben, including a book written about wild plants in Middle Europe that includes lots of recipes. Gatersleben’s staff made ten expeditions to Soviet Georgia within the last 12 years where they collected a substantial amount of plant material including a large collection of alliums. The Georgian genebank has recently been completely flattened by civil war, so a lot of that material has been lost and now exists at Gatersleben and also here at Heritage Farm. About five years ago, Seed Savers received a collection of about 80 garlics from Gatersleben, most collected in Soviet Georgia, and those garlics are still being maintained here at Heritage Farm in the garden right behind this barn. Take a look later.

Dr. Hammer and Dr. Hanelt gave us an extensive tour of Gatersleben which lasted nearly a day and a half. Dr. Hammer described Gatersleben’s history as a successful marriage of classical taxonomy and agronomy. Gatersleben is keeping an impressive collection of 350,000 dried herbarium specimens all taken at the flowering stage during their first reproduction, plus a spike collection of seedheads from all of their grains, and collections of dried pods and seeds from other food crops. (Their Mongolian and Chinese collections are kept separate in order to be more easily accessible.) Every one of their growouts is compared to the herbarium specimens, spikes, pods and seeds to make sure that they aren’t changing. We spent a couple of hours with the young scientist who does all of their computer work. Their greenhouse system is extensive and first rate, and their caging techniques were quite interesting. Right now they have four seed storage vaults – three right at freezing and one much colder – and are in the process of building other vaults that should about double their storage capacity. All of their seeds are stored in glass jars with glass tops that are not airtight and the rooms are not humidity controlled, but each jar contains a small mesh bag of silica gel that absorbs the moisture that leaks into the jar. The silica gel is color-indicating, so the mesh bags are visually monitored and redried as needed. The shelf life for various seeds that Dr. Hammer described was as good as techniques using heat-sealed airtight packets or humidity-controlled rooms.

If I can ever find the time, I hope to write an article for one of Seed Savers issues that describes everything we saw and learned. My impressions of Dr. Hammer and Gatersleben could fill many pages, but let’s just say that he is definitely someone that Seed Savers is proud to be working with, that Vavilov’s spirit is very much alive at Gatersleben, and that Dr. Hammer and his small staff are possibly the best plant collectors in the world. Joint projects involving Seed Savers and Gatersleben’s staff may prove to be our greatest contribution during this critical period.

For six years now, Seed Savers has received generous steady support from the Wallace Genetic Foundation, first in the form of challenge grants to our members for land acquisition here at Heritage Farm, and more recently in support of our international projects. That funding has made possible my three trips to Russia and two trips to East¬ern Europe, has brought Marina Danilenko to Heritage Farm from Moscow twice, Nancy Arrowsmith from Austria, Elchin Atababayev from Azerbaijan, and Teresa Kotlinska from Poland. (I’ll tell you about Elchin and Teresa in a minute.) That funding also made it possible to bring Nancy and Elchin with me last March so that the three of us could make a joint presentation to Gatersleben’s staff and technicians that was really quite well received. And that funding will also cover the costs of collecting expeditions in various Eastern countries next fall, which I will also talk about in just a minute.

As I already said, when Nancy Arrowsmith was here last summer, she told us that the richest areas and also the areas where we could probably make the greatest contribution would be Romania and Poland. And that is exactly what Dr. Hammer also told us at Gatersleben. Dr. Hammer said that Gatersleben’s collections from the mountainous regions of Poland are quite good, so we should concentrate on the foothills and flat¬lands. He also said that there has been very little collecting done in Romania, and that the Romanian genebank is still in its infancy. Within the last year, conditions have started to become rather dangerous in Romania for outsiders. Nationalistic conflicts are beginning to spring up in which the Romanians are trying to force out the Hungarian minority and also the gypsies. It’s probably already too dangerous for outsiders to col¬lect in Romania, but one of the scientists on Dr. Hammer’s staff is a young Romanian woman named Helga Rosso who is married to an Italian scientist. Seed Savers intends to fund a three-week collecting expedition in Romania by Helga Rosso that will occur during September. She’ll be collecting in the Bucovina region in the foothills of the Transylvanian Alps for three weeks during September, and the material that she collects will be entered into the seedbank at Gatersleben and a duplicate collection will also be sent to Heritage Farm for maintenance.

On that same trip to Gatersleben last March, we took the night train from East Berlin to Warsaw, Poland, where I spoke to students at the Agricultural University. We were hosted by Professor Gorny, a really wonderful fellow who is almost singlehandedly responsible for the organic farming movement in Poland. Professor Gorny had one of his students drive us in his car about 50 kilometers southwest to the city of Skierniwice, where several large agricultural breeding projects are located. There we met Teresa Kotlinska, who’s our guest here today and who will be speaking next. We found out about Teresa from Renée Vellvé, who works for GRAIN in Barcelona and wrote Saving the Seed, an excellent book that traces the decline of genetic diversity in European agri¬culture. Several chapters of Saving the Seed have just been reprinted in Seed Savers 1993 Summer Edition. But I could also have found out about Teresa if I’d just talked a little more closely with John Swenson. Several years ago John was part of a month-long expedition of scientists from the University of Wisconsin at Madison who traveled to Central Asia to collect wild onions in the Tian Shan Mountains just north of Iran and Afghanistan, and one of the foreign scientists on that expedition was Teresa. It’s truly a small world.

From the moment Nancy and I met Teresa, and her two co-workers, our conversation quickly made it obvious that she was quite concerned about the fate of traditional food crops as Western agricultural technology and hybrid seeds poured into Poland. Teresa had already collected about 300 traditional varieties on her own. She collects by going into rural villages and asking to meet the old woman who supplies everyone with the old seeds. Usually she finds an elderly woman who is keeping a large collection of vegetables, flowers, medicinals and perennials. The seeds are always given for free, because the old people are concerned that their traditional varieties are in danger of dying out. Teresa also tries to collect histories and recipes along with the seeds. Seed Savers intends to fund 30 days of collecting by Teresa in rural areas of Poland during August, September and October. Again, we’ll make sure that these seeds get into the Polish genebank, and that duplicates are also sent to Heritage Farm for maintenance.

We are also working with a young man from Azerbaijan named Elchin Atababayev, who accompanied Nancy and me to Gatersleben. I met Elchin during my first trip to Mos¬cow for a large environmental conference in March 1991. Elchin is a geneticist with the Institute of Genetics and Selection in Baku. Azerbaijan lies between two major mountain ranges of the Caucasus and is incredibly rich botanically. The country is blessed with a wet mountainous topography that ranges from above 15,000 feet in the west, down to below sea level at Baku, the capital, in the east. There’s an incredible range of microclimates, all the way from zone 4 to zone 9, which is the equivalent of Minnesota to northern Florida. When I first met Elchin, the rapport between us developed very quickly, just as it did with Teresa. Elchin told me about collecting with the scientists in his Institute and lamented, “They see endemic varieties only as breeding material. I see them as much more. I see them as living books reaching back through time.”

Elchin and the other scientists at his Institute had already collected traditional varieties all over Azerbaijan, but unfortunately that material was stored it in an agricultural station in Nagorno-Karabach, an Armenian enclave in the western mountains of Azerbaijan. Ever since Azerbaijan declared its independence during the failed Russian coup in August 1991, there has been fierce fighting between Russian soldiers hired by the Azerbaijani government and Armenian soldiers along with mercenaries from a half a dozen different countries. All 200,000 Armenians fled back to Armenia within the first few months, but the fighting, which is now over oil reserves, rages on. First, the Armenians used the agricultural station where the seeds were stored as their troop headquarters, until they were driven out, and then the Russians used the station as their troop head-quarters, so the collections of seeds have been completely destroyed. Also, before they fled, the Armenians cut down all of the orchard collections so that the Russians couldn’t use them for food. Nagorno-Karabach covers only about ten percent of Azerbaijan, but missiles tipped with shrapnel and phosphorus are raining down over the entire western half of the country. And recently Armenia re-invaded Azerbaijan which further escalated the conflict and will probably prevent me from making a trip there next fall to speak at the University, at the Agricultural Academy and at Elchin’s Institute.

That type of nationalistic conflict is starting to rear its ugly head all across Eastern Europe and the former Soviet republics. As I said, those problems are just starting in Romania, and of course we hear almost daily about the fighting in what used to be Yugoslavia. Elchin said that each valley in Azerbaijan is inhabited by a different tribe that speaks a different dialect, all are heavily armed and all of them hate the tribes in the neighboring valleys. There are 130 distinct nationalities in the former Soviet Union and, until just two years ago, the iron grip of Soviet totalitarianism was all that kept them from fighting. I am really afraid that we are going to see those types of nationalistic conflicts sweep across that whole area, and such fighting has already destroyed the seed banks in Georgia and Azerbaijan.

Last August we brought Elchin to Heritage Farm after the Campout to learn about Seed Savers projects. We also took him down to Ames, Iowa to meet my friend Mark Widrlechner and to tour the Plant Introduction Station which is probably the best in the U.S. system. Before he left, we supplied Elchin with really minimal funds, but enough for him to go back and hire the assistant director of his Institute and another woman scientist to re-collect some of the plant material that has been lost in Azerbaijan. And some of those traditional seeds are now starting to flow into our collections here at Heritage Farm.

We are also working with a young Russian woman named Marina Danalenko. Three years ago Marina and her mother – who is a tomato collector – started the first private seed company in Moscow and a similar company in their home city in the Urals. All vegetable seeds in the former Soviet Union used to be produced by a network of collective farms, and those seeds were sold, for example, in seven State seed stores in Moscow, and in similar State seed stores in cities throughout the former Soviet Union. Marina and her mother were buying seeds from that network and then paying pensioners to fill packets. By the time we met Marina, she was already sending out price lists to 80,000 Russian gardeners each year and selling about 500,000 packets of seeds through the mail. She would put notices about her company in newspapers and magazines, gardeners would send her their names and addresses, then a price list was sent that the people used to place their orders, the seeds were sent out sort of C.O.D. and then the Russian postal system would rip Marina off. She has persevered, but it’s been really difficult for her. Also, last summer Marina actually contracted with the Moscow branch of the Vavilov Institute to grow out some of her vegetable seeds, because, as she says, the staff is highly professional, their seeds are finest quality, and the Institute certainly needs the money.

Last January Yeltsin was forced to accept a conservative Prime Minister, a throwback to the Brezhnev era, who immediately put a new taxing system into place designed to kill all private initiative in Russia. Marina and her mother had been working with five other people the previous year, and their five friends all broke off and started their own private seed companies last year, but the new taxing regulations killed all five of the new initiatives. Marina’s company was the only one that survived, and it has survived partly because Seed Savers has been helping her to a certain extent. During each of the last two years, we have brought Marina over to the U.S. to visit Heritage Farm. On her first trip I also sent her to visit my friend Rob Johnston at Johnny’s Selected Seeds in Maine, and also down to meet Jeff McCormack who runs Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, a small seed company in Charlottesville, Virginia. Rob put Marina to work for half a day in each of the different departments at Johnny’s. Marina’s visits to those two companies gave her a mind-blowing twenty-year glimpse into her future. The effect on her was really amazing! You know, I don’t think there is anything we can do that is more powerful than bringing Easterners here to see our projects. They have plenty of enthusiasm, but they have no context, no background information concerning how to go about things. Getting the right information to specific projects can facilitate years of progress in a matter of months.

Marina has already brought us 170 different Russian tomatoes, including many traditional varieties that people haven’t seen for at least the last seventy years, if ever. Those tomatoes are all growing here in Heritage Farm’s gardens this summer. We were hoping to evaluate and photograph all of them, but the nearly constant rain has caused the plants to perform oddly, so we haven’t been able to tell as much about them as we had hoped. Our collections of tomatoes here at Heritage Farm now number about 3,000, and over the last six years David Cavagnaro and his garden crews have probably grown 1,500, if not more. Recently David told me that it was getting to the point where nothing was really coming into the collections that he hadn’t already seen. Well, within the last year that has changed dramatically, due to the material that’s now arriving from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. There are black tomatoes, tomatoes that have a blush on their cheek like a peach, two-celled tomatoes, and much more. We are working with Marina in an ongoing relationship to try to collect traditional varieties throughout Russia, and also to buy commercial quantities of seeds produced in Russia and the former republics.

Probably the greatest difficulty with this type of international rescue program is to make sure that the material is also maintained within each country, not just here at Heritage Farm. The continued existence of traditional varieties in their own homelands will be, by far, the most difficult and most vital part of SSE’s efforts, because maintaining endangered collections at Heritage Farm is a temporary solution at best. Long-term success depends on overcoming really immense problems, such as how to assure that at least some pockets of traditional agriculture remain untouched during the rising flood of Western agricultural technology and hybrid seeds. During the short term, however, maintenance at Heritage Farm will be vital in order to keep endangered collections of seeds alive during periods of intense turmoil in various countries. This rapid influx of international varieties will include plants from a wide range of temperate climates, but we should be able to overcome any problems by utilizing a similar range of SSE growers, enlisting the help of SSE’s network of curators, and developing long-term working relationships with other major garden projects such as Native Seeds/SEARCH.

The best examples of maintenance and redistribution are efforts by Gary Nabhan and his friends at Native Seeds/SEARCH, which has collected, maintained and returned traditional Indian food crops throughout the desert Southwest. Gary and his co-workers travel to remote mountain villages deep in Sonora, collect the seeds of food crops that have died out on reservations north of the border, and then maintain the varieties within the membership of Native Seeds/SEARCH until the various tribes are ready to reclaim them. I’ve watched Gary do this work for a dozen years, patiently working to build interest in native crops until the young Indians were again strong enough in their traditions – praying and gardening together – to want their seeds back. One part of Native Seeds/SEARCH functions like a seed company that sells to Southwestern gardeners with profits going to support their preservation work, including some really interesting “in situ” (on site) efforts that effectively prop up traditional agriculture in Mexico by agreeing in advance to return the next year and buy farmers’ crops. It is also quite interesting that Marina Danilenko described a somewhat parallel process that she has watched in Russia, where for about the last ten years everything Western was thought to be superior, before the Russian people again realized that their seeds were best for their conditions. Now the Russian people are also starting to reach back, again trying to find the food crops that they hope haven’t been lost. There are endless parallels between Gary’s work and Seed Savers’ efforts involving traditional seeds belonging to nationalities throughout Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

Ever since my first trip to Moscow in March 1991, I have been puzzling through scores of schemes that might be capable of financially supporting significant genetic preservation efforts in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. In my opinion, the only plan that is capable of providing long-term self-support would be to purchase and import inexpensive vegetable seeds grown in Eastern countries, sell those seeds here in the U.S. where prices and interest in unique seeds are high, and then return the profits overseas to support additional collecting and maintenance. A couple of months before last Christmas, Seed Savers developed a four-page catalog of books and products that were sold to our members, which was quite successful. A similar brochure will be mailed next October, in which we intend to test the waters by offering a gift collection of six traditional Russian vegetable varieties, and, if that is successful, a year later we will introduce several collections of traditional seeds from other former Iron Curtain countries. Our goal is to generate enough support, so that five years from now we will not have to rely entirely on grants. We hope that five years from now the sales of gift collections of traditional seeds from many countries will be able to support all of Seed Savers international efforts and also the maintenance of endangered foreign collections at Heritage Farm.

We’ve been steadily building Seed Savers’ projects for 18 years and have developed a formidable array of resources, which include a dedicated membership of 7,000, incredible collections of traditional vegetables and fruits, and genetic preservation projects at Heritage Farm that are capable of maintaining thousands of varieties of food crops. Our annual growouts at Heritage Farm produce much more seed than is needed just to maintain our collections, so during the last few years we have been sending out large amounts of excess seeds to hunger projects here in the U.S. and abroad. Also, because of the success of Heritage Farm’s preservation projects, we find ourselves uniquely well-positioned to make a significant contribution to rescuing genetic resources in different areas of the world. I am pleased that we have been able to take Seed Savers’ work to an international level so quickly. This is really just the logical extension of the valuable work that we have been doing, and will continue to do, in North America. I am quite pleased that we currently find ourselves so well positioned to make such a valuable contribution at exactly the same time that these unique opportunities are opening up in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. This is the work that really excites me. I’m also quite certain that Seed Savers’ members will be equally excited by the unique seeds that will become available to them in the coming years.